Interpreting Blood Results: Why 'Normal' Isn't Always Optimal – A Nutritionist's Guide to Preventative Health

As a certified practising nutritionist in Australia, I've spent years helping clients decode their blood test results in ways that go far beyond what a standard GP visit offers. If you've ever left your doctor's office with a pat on the back and the words, "Everything looks perfect," only to feel exhausted, foggy-brained, or inexplicably unwell, you're not alone. That's because pathology lab reference ranges, those "normal" bands printed on your results, are often based on averages from the general population, including people who are already on the cusp of chronic conditions. They're not designed for optimal health; they're more like a safety net for acute illness.

At FROM WITHIN, I use "healthy reference ranges" derived from studies of truly thriving individuals - athletes, long-lived populations, and those free from metabolic or inflammatory burdens. These ranges are tighter, more proactive, and focused on prevention. Why? Because by the time your markers dip outside lab normals, the damage might already be underway. Subtle shifts, such as a slowly declining eGFR, a TSH creeping above 2 mIU/L or with a downhill trajectory past 1 mIU/L, or an HbA1c edging toward 5.5%, can signal an impending chronic issue such as kidney decline, thyroid dysfunction, or insulin resistance. My goal is to spot these nuances early, intervene with targeted nutrition and lifestyle tweaks, and reverse the trajectory before symptoms take hold.

Take one of my recent clients, Sarah (not her real name), a 52-year-old executive on multiple medications for blood pressure and cholesterol. Her GP assured her results were "fine", but her eGFR had been steadily dropping from 95 to 83 mL/min/1.73m² over two years – below the optimal >90 threshold I use for kidney health. She wasn't symptomatic yet, but ignoring this could accelerate toward chronic kidney disease. Similarly, her TSH sat at 3.2 mIU/L, within lab normal (0.5-5.0), but well above my optimal 1-2 mIU/L range, correlating with her unexplained fatigue, hair loss and weight gain. Her doctor dismissed it; I saw it as a red flag for subclinical hypothyroidism (Garber et al., 2021). Within months of a nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory protocol – rich in selenium, iodine, and cruciferous veggies, plus my compound for Divine Skin & Hair, her eGFR stabilised, TSH dropped to 1.8, her and skin and hair improved dramatically, plus her energy returned. This is preventative medicine in action: catching the whisper before it becomes a shout.

In Australia, where cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death, claiming around 43,800 lives annually (Heart Foundation, 2025a), we can't afford to wait. Nutritionists like me, bridge the gap between reactive GP care and true longevity. We track trends over time, not snapshots, and aim for biomarkers that reflect vitality, not just absence of disease. In this article, I'll walk you through key biomarkers across metabolic, cardiac, hormonal, and inflammatory health. I'll share the lab "normal" vs. my "optimal" targets, why they matter, and how small changes signal big risks. Let's empower you to interpret your results like a pro.

The Power of Trends: Why Tracking Matters More Than a Single Test

Before diving into specifics, understand this: one blood test is a photo; quarterly or annual tracking is the movie. Labs fluctuate due to hydration, stress, or even time of day, but trends reveal the story. Use a simple spreadsheet or app to log your numbers – date, value, and notes on diet/exercise. In Australia, access affordable tests via bulk-billed pathology or services such as i-screen. Aim for baselines now, then retest every 3-6 months if you're at risk (family history, age 40+, or sedentary).

Preventative nutrition isn't about restriction; it's strategic fuelling. For instance, if your fasting glucose trends upward (even within 4.0-5.5 mmol/L lab normal), it might hint at early insulin resistance. A low-GI Mediterranean-style diet – think quinoa salads, fatty fish, and berries, can nudge it back. The payoff? Reduced risk of metabolic syndrome, which affects approximately 1 in 3 Australian adults (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024) and triples heart disease odds if unchecked (Shah, n.d.).

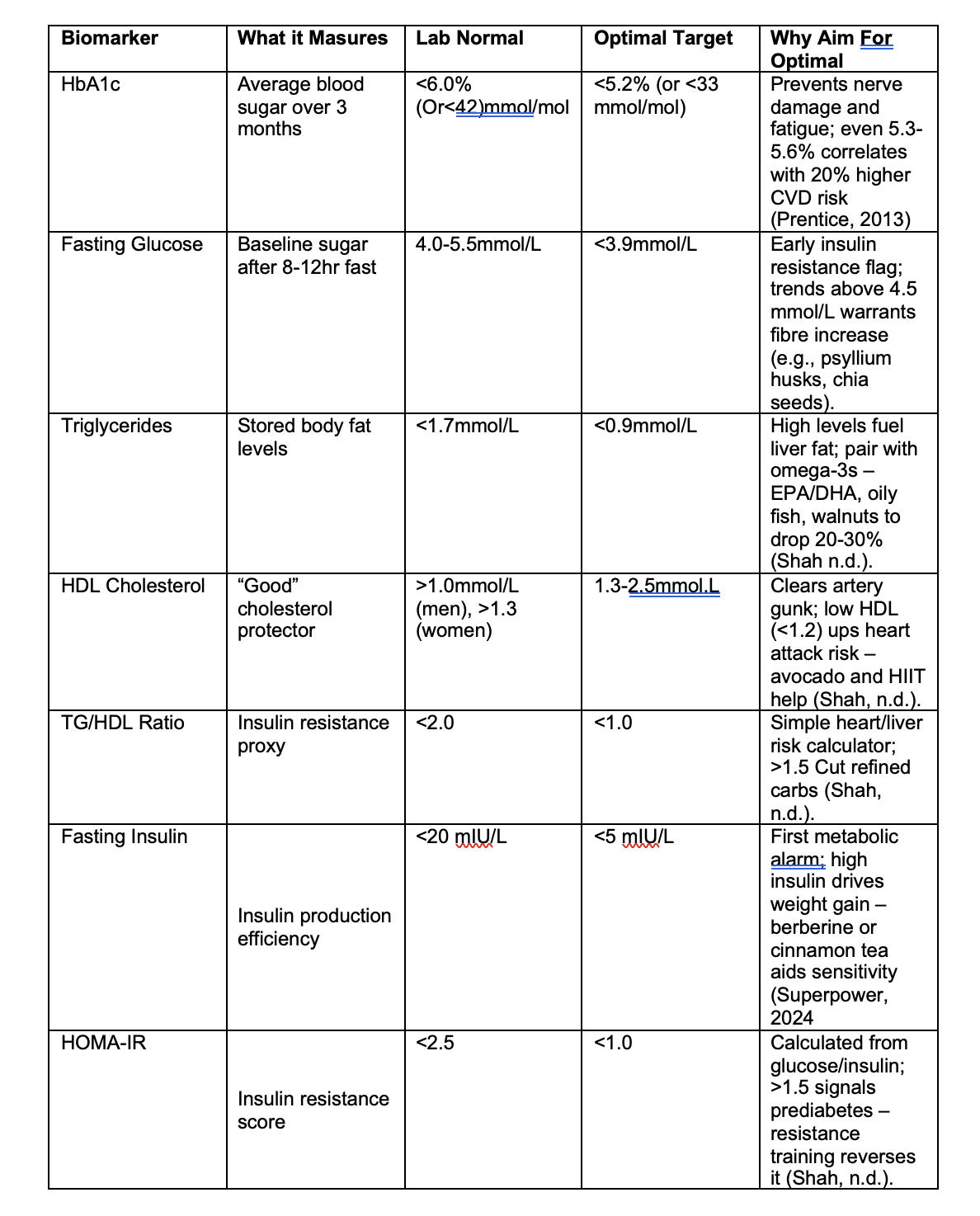

Metabolic Health: Fuel for Your Engine

Metabolic markers are your body's efficiency gauges. Elevated blood sugar or lipids don't just flag diabetes; they silently promote artery plaque, years before diagnosis. Lab ranges often tolerate mediocrity, but optimal ones, drawn from centenarian studies such as the Blue Zones, keep you on track to an extended healthspan. Here's a snapshot to what you should be tracking:

In practice, I see clients with "normal" HbA1c at 5.6% dismissed by GPs, yet they're battling afternoon crashes. Optimising to <5.2% via stable-protein meals stabilise energy and supports long-term glucose control (American Diabetes Association, 2024). If you’re overweight or stressed, this should be tracked quarterly to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome.

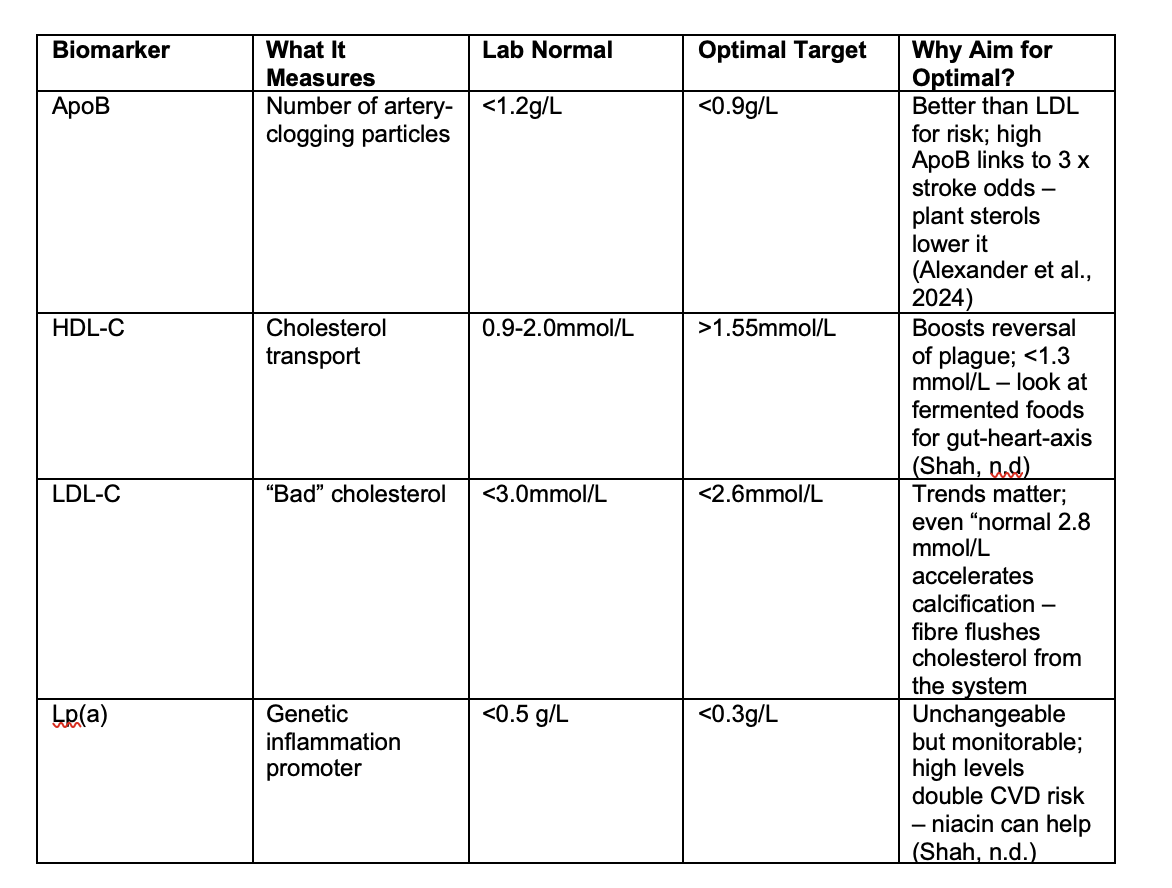

Cardiac Health: Guarding Your Vital Pump

CVD kills more Australians than anything else (one every 12 minutes; Heart Foundation, 2025a). Cardiac markers aren't just cholesterol; they're plaque predictors. Lab normals overlook genetic factors such as lipoprotein a or Lp(a), which affects 20% of us and isn't routinely tested. Optimal ranges from functional medicine research, emphasise balance for arterial youthfulness.

Hormonal Health: Balancing Your Inner Symphony

Hormones orchestrate energy, mood, and metabolism. Australian reference ranges often flag extremes only, ignoring subclinical dips that cause "adrenal fatigue" or thyroid symptoms. Optimal ranges from endocrine studies prioritise resilience, especially post-40 years when declines accelerate (Shah, n.d.).

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone is one where lab normals range 0.5-5.0 mIU/L, but optimal is 1-2 mIU/L. This is crucial to preventing autoimmunity, noting that Hashimoto risk jumps at >2.5; Garber et al., 2021.

For women, oestrogen "depends" on cycle phase (follicular: 110-330 pmol/L optimal), with fluctuating hormones causing imbalances that can drive PMS or peri-menopausal symptoms.

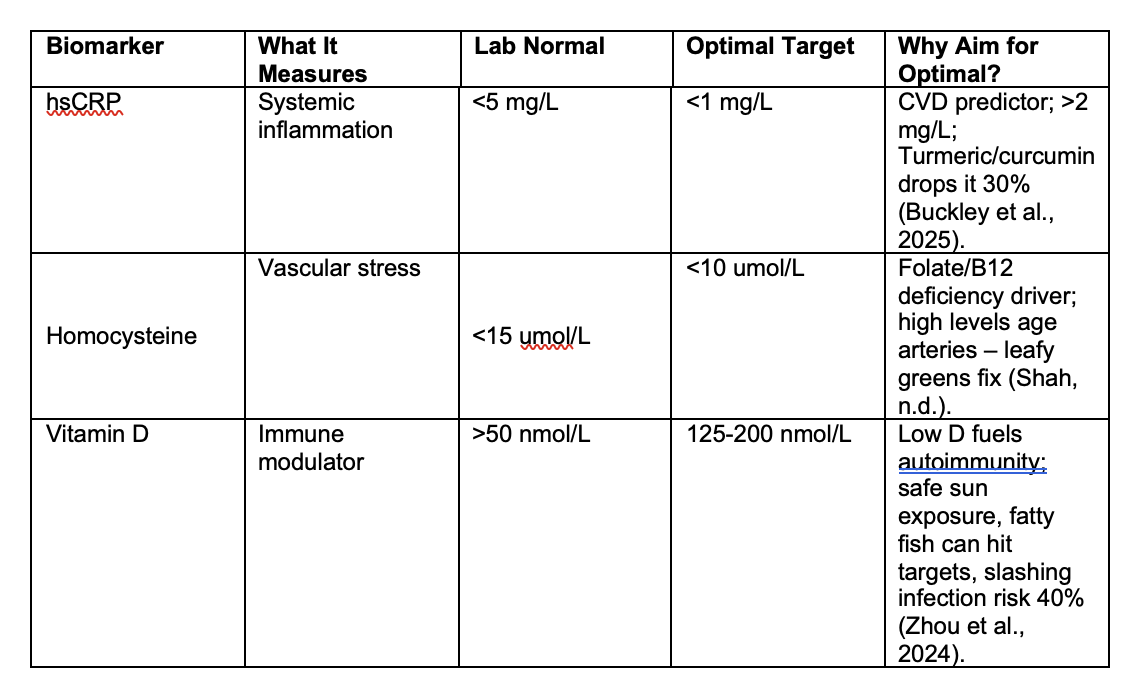

Inflammation and Beyond: The Silent Saboteur

Chronic low-grade inflammation underpins more than 50% of deaths worldwide from major diseases (Furman et al., 2019). Markers such as hsCRP rise silently from gut dysbiosis or stress. By recognising optimal ranges, one can address this early, keeping systemic and/or chronic inflammation in check.

Add eGFR: Lab >60 mL/min/1.73m², optimal >90. Declines signal nephrotoxic meds or dehydration – hydrate with electrolytes, add kidney herbs such as dandelion (Shah, n.d.).

Physical metrics amplify this: Waist <94 cm men/<80 cm women (optimal <89/<72 cm); bioimpedance for <25% body fat; monthly BP averages (Shah, n.d.).

From Insight to Action: Your Preventative Playbook

Interpreting your blood results optimally isn't daunting—it's empowering. Take charge as the CEO of your own health by starting with a comprehensive blood panel. You can track trends yourself, or book an appointment with me, where I'll log and analyse your results, creating a personalised nutrition plan based on optimal ranges. This includes tailored dietary and lifestyle strategies, along with targeted nutraceuticals to extend your healthspan.

Remember, while pharmaceutical medications often treat symptoms, nutrition addresses the root causes.

Ready to extend your health? Book a consult here and let's transform your "normals" into optima. Your future self will thank you.

References

Alexander, D. D., Kabir, S., Silvis, R., & Boffa, M. B. (2024). An expert clinical consensus from the National Lipid Association. Journal of Clinical Lipidology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2024.09.004

American Diabetes Association. (2024). 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care, 48(Supplement 1), S27–S44. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc25-S002

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2024). Heart, stroke and vascular disease: Australian facts. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/hsvd-facts/contents/summary

Buckley, L. F., Dixon, D. L., & Wohlford, G. F. (2025). High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: Measure or not? US Cardiology Review, 19, e02. https://doi.org/10.15420/usc.2024.02

Furman, D., Campisi, J., Verdin, E., Carrera-Bastos, P., Targ, S., Franceschi, C., Ferrucci, L., Giaimo, T., Goronzy, J. J., Hansen, M., Martin, G. S., Mooney, M. R., Sebastiani, P., Swedlund, N., & Yashin, A. I. (2019). Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature Medicine, 25(6), 1822–1832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0

Garber, J. R., Cobin, R. H., Gharib, H., Hennessey, J. V., Klein, I., Mechanick, J. I., Pessah-Pollack, R., Singer, P. A., & Woeber, K. A. (2021). Hypothyroidism: Diagnosis and treatment. American Family Physician, 103(10), 605–613.

Heart Foundation. (2025a). Key statistics: Cardiovascular disease. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/your-heart/evidence-and-statistics/key-stats-cardiovascular-disease

Heart Foundation. (2025b). Key statistics: Heart disease. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/your-heart/evidence-and-statistics/australia-heart-disease-statistics

Prentice, R. L. (2013). Diabetes prevention: Keeping HbA1c under 6.5% is a good goal. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 1(2), 90–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70043-9

Shah, D. (n.d.). Tracking your critical biomarkers. Next Health. Retrieved September 18, 2025, from https://www.drshah.com/biomarkers

Superpower. (2024). Optimal fasting insulin. https://superpower.com/editorial/optimal-fasting-insulin

World Health Organization. (2023). Hypertension. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension

Zhou, Y., Mu, Y., Li, J., Chen, H., Luo, L., & Liu, X. (2024). Optimal methods of vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: A GRADE-assessed systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Nutrition Journal, 23(1), Article 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-024-00990-w